Unmasking the-RSS-for the Masses- A R Vasavi

[“RSS Aala mattu Agala”- Review by A R Vasavi in “The book Review Literary Trust” September 2022 issue…ದೇವನೂರರ “ಆರ್.ಎಸ್.ಎಸ್. ಆಳ ಮತ್ತು ಅಗಲ” ಕೃತಿಯನ್ನುಎ.ಆರ್.ವಾಸವಿಯವರು ವಿಮರ್ಶಿಸಿದ್ದು, “The book Review Literary Trust”ನ ಸೆಪ್ಟೆಂಬರ್ 2022ರ ಸಂಚಿಕೆಯಲ್ಲಿ ಪ್ರಕಟವಾಗಿದೆ.]

In the new lows that we have reached in our national public lives, none has been as troubling as the self-imposed silence by many writers on the depredations of the RSS and the BJP. Of those who do write critically, about the multiple erosions of our democracy and cultures, it is to a consenting audience or as in the English academia it is in the language of liberal social sciences. Amidst all this, the ability to reach out to the larger society, now on the threshold of a mass society, and speak to its varied members in idioms and terms that they can understand about the troubling trends in the nation, the implications of the loss of democracy, pluralism, secularism and an overall sense of collective forbearance has been very limited.

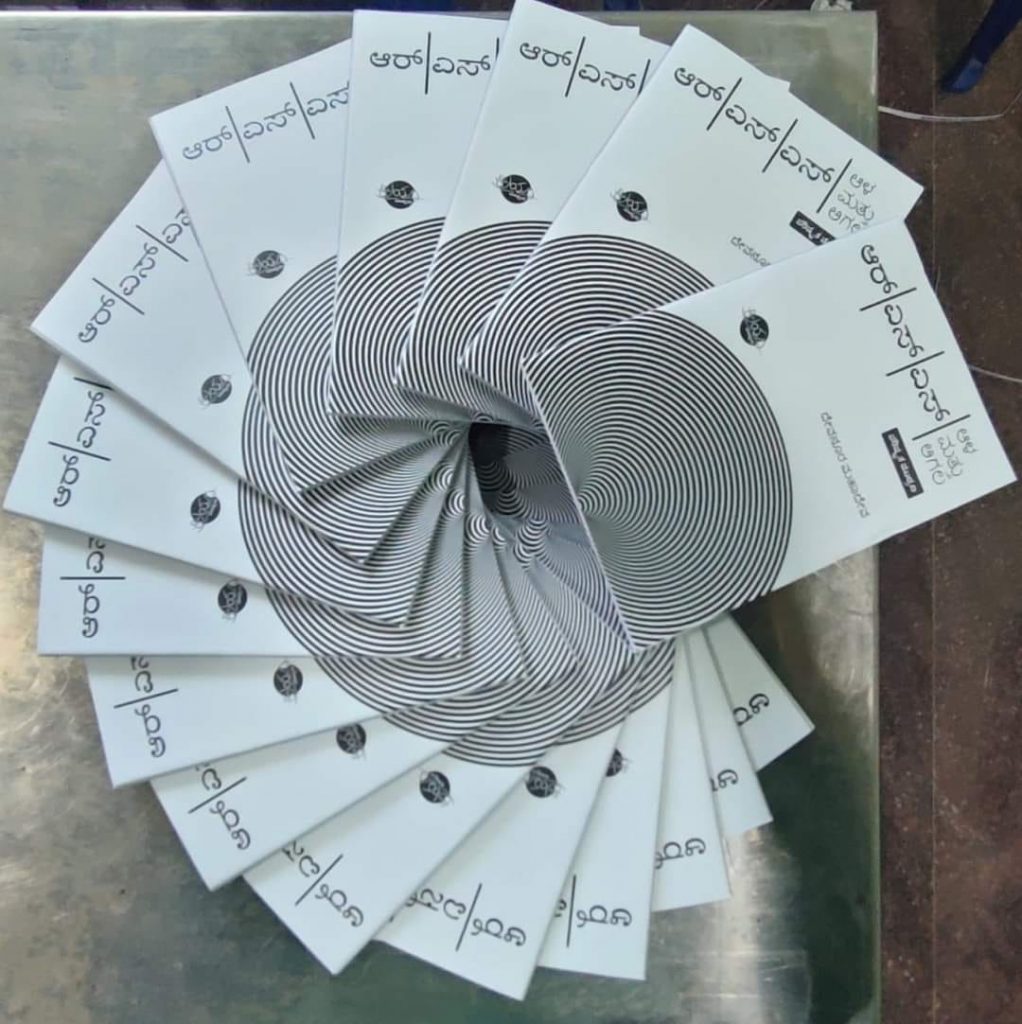

Devanoor Mahadeva’s Kannada booklet, RSS: Aala Matthu Agala overcomes this key limitation and he deploys idioms, imagery, and narratives derived from folklore and rural culture to provide an accessible critique of the RSS. Going beyond the now standard construction of the rise and rise of the BJP as being driven by the Shah-Modi ‘double-engine’, Devanoor casts his observant eye and literary skills to lay bare the ‘innards’ (antara) of the RSS which in reality is the ‘life-force’ (prana) behind the onset of ‘total authoritarianism’ (sarva sarvaadhikara) in the nation. In critically reviewing its historical antecedents and pointing to its current impact and future implications, Devanoor unpacks the ‘width’ of the RSS’s reach into our societies. By laying out the multiple ways in which the RSS has laid siege to the foundational structures of the nation, he portrays the dangerous ‘depth’ that it has reached. That the booklet (facilitated by a publishing arrangement that encourages both multiple and local publication and subsidized rates for bulk sales) has sold one lakh and six thousand copies in the first month of its publication is testimony to the author’s ability to speak to the people and lay bare the machinations of an organization that has created ‘trouble, suspicion, and hate’ (gondala, anumana, dvesha) in our national life.

Portraying the need to ward-off the RSS just as rural culture does the small-pox deity that portends disease and death, Devanoor unmasks the organization which like a ‘trickster’ (mayavi) has been disguising itself in unlimited and unanticipated ways. What he sees in only a brief glance is itself a ‘terrifying vision’ (ghora drshya). Devanoor traces the source of this terrifying vision and its impact to some of the foundational perspectives that Golwalkar and Savarkar, who as ‘gurus, philosophers, and guides’ have laid out for the RSS, and their ambition of forging Hindutva in the nation.

Through their celebration and endorsement of the Chaturvarnas and the Manusmriti, Devanoor elaborates, the ‘founding fathers’ of the RSS have reified the caste system, dismissed the Constitution, and asserted the supremacy of a constructed ‘Aryan’ race. In spreading this ‘poison seed’ (visha beeja), they have sought to dismantle federalism and thereby the different identities of regional States. In eviscerating regional cultures and their constitutional rights, the RSS seeks to centralize power. Critiquing Golwalkar and Savarkar’s endorsement of Hitler and his extermination of Jews as agendas for fulfilling ‘racial pride’ (janagiya abimana), Devanoor cautions readers about how violence is legitimized. He goes on to note that, ‘For the RSS, pluralism itself means fission’, a poison seed…Golwalkar’s call to establish authoritarian government is to rewrite the Constitution. Not only that, like Hitler’s principles of authoritarianism he calls for one flag, one national rule, one race, and one leader’ (pp. 15-16).

The result of all this, Devanoor elaborates, is that in our contemporary times, these ideas and principles have been realized through the many agendas in which the RSS’s diktats that require complete and blind obedience from its members have led followers to lose their ‘thinking capacity’ (vivechana shakti), and become dehumanized so that they are rendered into being ‘inhuman robots’ (amanaviya robotgalu) and carriers of a ‘tide of hate’ (dveshada samara). Devanoor lists the failures of most political parties which by being either family or single person-based, or by drawing on their politics that is ‘extra-constitutional’, have failed to be accountable to the electorate. Similarly, he unpacks the reasons for the Dalits and other backward castes to have fallen into the mesmerizing trap of the RSS and to have become its foot soldiers. Using Modi as their ‘ceremonial god’ (utsava murthi), who has been enthroned to power (through the false promises of transferring re-claimed black money into the accounts of citizens, increasing farmers’ income, and generating employment) and the large number of members who are ‘puppets’ (thogalu bombe), the RSS has implemented its agenda of Hindutva. Declaring Pakistan as its ‘eternal enemy’, targeting Muslims and Christians as hostile to Hindu culture, fomenting tension and violence between communities, hate has become a dominant narrative. Devanoor goes on to elaborate how the RSS-BJP alliance has led to the pauperization of India by privatizing public assets, increasing debts, and deploying devastating economic policies such as demonetization. The result is ‘terrifying inequality’ (bikhara asamanate) in which the nation ‘flies around like a kite without its thread’ (p. 37) while the RSS-BJP continue to ‘chant nationalism’ (deshaprema japisuta) and usher in varied laws.

Devanoor focuses on the impact of such legislations in Karnataka where the passage of the anti-conversion Bill has sought to erase the rights of people to religious freedom and thereby the plurality of ‘religions, sects, and spiritual traditions’ (p. 50), while distortions of school texts have led not only to reversing historical truths but also to iconizing figures such as Savarkar and Godse. Ruing the negative implications of all this for the unity of the nation, Devanoor flags the loss of social justice, especially to Dalits and Adivasis, as trends that will grievously affect the most marginalized. The renaming of Adivasis as ‘Vanvasi’ is identified by Devanoor as one more strategy deployed by the RSS to deny Adivasis/tribals their rights to be recognized as indigenous people. To challenge such trends that have resulted in the ‘nation ailing’ (bharata narulutide), while the RSS and its affiliates are ‘roaring’ (abharisu), Devanoor concludes by calling for urgent and collective action.

‘At least now, those organizations, groups and parties that seek to move society forward must put aside their own small limitations and flow together as one river. For this, they must also cast aside their own disease of superiority. And also discard their egos. They must have the humility to accept that there have to be hundreds of pathways until the goal is reached. The rigidity of leadership should be shed. Instead of the small mindedness that asserts the importance of only their ways and their organizations, we must, for the sake of saving the principles of the Constitution, for India’s pluralism that is its life, and for retaining a collective system, and for its inclusive and participatory democracy, without the mentality of hierarchy, and to realize a culture of love, equality, and co-existence, come together. Justice must be kept alive in society. Everybody should be able to lead integrated lives in their societies and communities so as to be revitalized. New social paths must be gained’ (pp. 61-62).

His final words are a clarion call against ‘hate, intolerance, and ignorance‘ (dvesha, asahane, moudya) which when unchecked and unleased will be like the ‘demon of hate’ (dvesha pishachi) and will devour not only its own ‘creator priest’ (pitamaha mantravadi) and the followers but also all of us. He concludes by asking us to bear this in mind and ‘walk together’ to address such depredations.

Unlike some of the earlier English tracts that have highlighted the march of the RSS, Devanoor’s booklet presents the significance of the RSS in a cultural idiom that can resonate with a broad spectrum of people. Although shorn of theoretical jargon, Devanoor is able to underscore, as did Gramsci, how false consciousness and hegemony are processes by which agendas that are antithetical to the interests of the people are supported by the people themselves. In linking the philosophy, personality, politics, and cultural strategies of the RSS to the growing authoritarianism, hate, communalism, and myriad forms of violence in the nation, this booklet has the potential to be a source for resistance against the ‘magical tricksters’ and their deceptive narratives. The need to keep the tract a short and succinct one may be the reason for the author to not mention the grievous violation and misuse of the legal systems that have led to the incarceration of hundreds of activists, including the Bhima-Koregoan 16. That the killing of Dabholkar, Pansare, Kalburgi and Gauri Lankesh are not mentioned is perhaps a strategy to be focused on the more insidious ways in which the RSS impacts the average person. Devanoor’s booklet signals the need for more such writing in all the languages of India to both unmask and interpret the impact of the RSS in all its depth and width. Since Karnataka has become the ‘gateway’ to the RSS-BJP rise in the South and to the intensified forms in which Hindutva is driving both politics and public culture, it is perhaps only apposite that the cultural and political strategies by which the RSS juggernaut must be halted is to come from Karnataka itself.