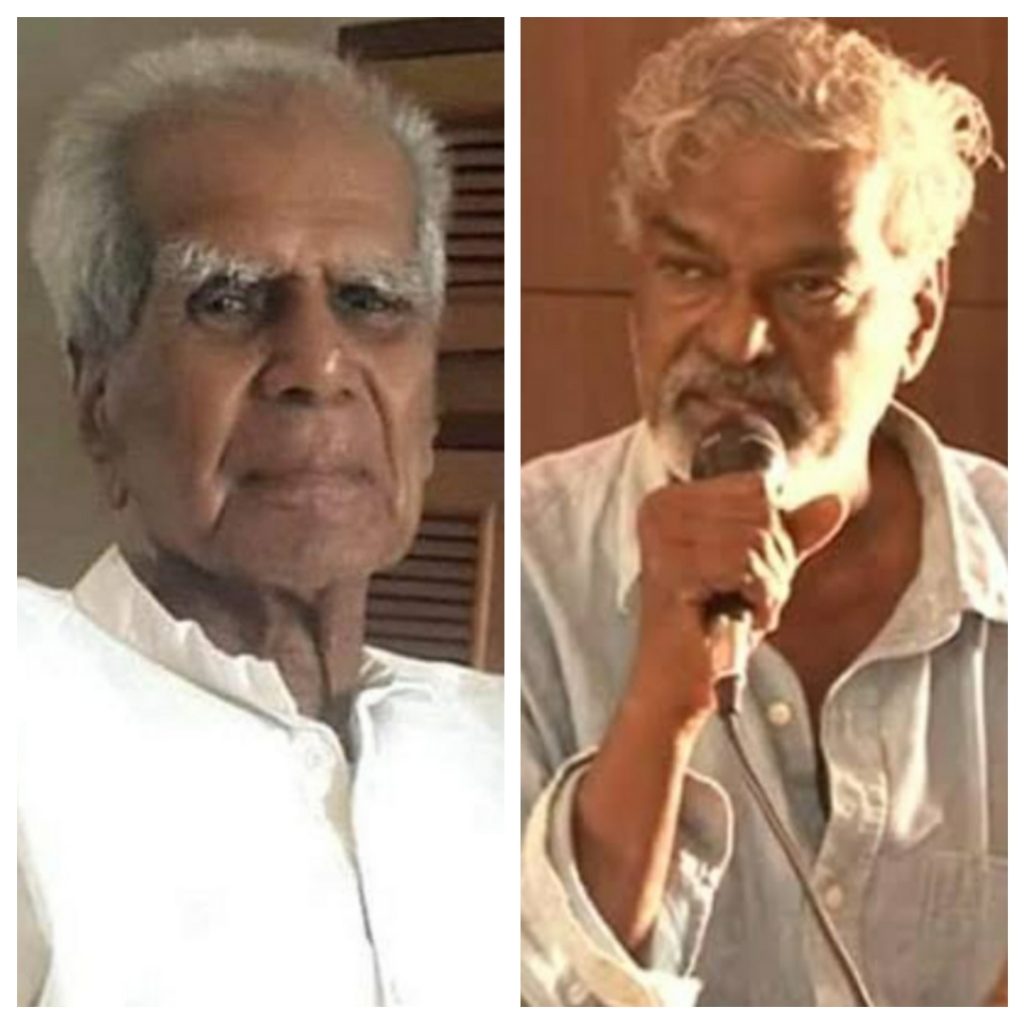

DEVANURA MAHADEVA AND DALIT SENSIBILITY -G.S.Amur

[Renowned critic G.S.Amur was written review of the works of Devanura Mahadeva and it was published in the book- ‘Essays on modern Kannada literature’ by Karnataka Sahitya Akademy. Our Heartfelt thanks to critic V.L.Narasimhamurthy for finding this article and sending it to ‘Namma Banavasi’ and to poet Sanghamitre Nagaraghatta for typing it][ಕರ್ನಾಟಕ ಸಾಹಿತ್ಯ ಅಕಾಡೆಮಿ ಮುದ್ರಿಸಿರುವ ‘Essays on modern kannada literature’, ಕೃತಿಯಲ್ಲಿ ಖ್ಯಾತ ವಿಮರ್ಶಕ ಜಿ.ಎಸ್.ಆಮೂರ್ ಅವರು ದೇವನೂರ ಮಹಾದೇವ ಅವರ ಕೃತಿಗಳ ಕುರಿತು ಮಾಡಿರುವ ವಿಮರ್ಶೆ ನಮ್ಮ ಮರು ಓದಿಗಾಗಿ ಇಲ್ಲಿದೆ. ಇದನ್ನು ಹುಡುಕಿ ‘ನಮ್ಮ ಬನವಾಸಿ’ಗೆ ಕಳಿಸಿದ ವಿಮರ್ಶಕ ವಿ.ಎಲ್.ನರಸಿಂಹಮೂರ್ತಿ ಮತ್ತು ಬೆರಳಚ್ಚು ಮಾಡಿ ಕೊಟ್ಟ ಕವಿ ಸಂಘಮಿತ್ರೆ ನಾಗರಘಟ್ಟ ಅವರಿಗೆ ಹೃದಯಪೂರ್ವಕ ವಂದನೆಗಳು]

Devanur Mahadeva (b.1948) is not a prolific writer. His literary output is limited to just three books Dyavanuru (1973) a collection of seven stories, odalala (1978), a short novel and Kusumabale (1988) the novel which won for him the Sahithya Akademi award. But no other Dalit writer has proved to be as influential as he in the post Navya period. There are two reasons for tthis: his unparalleled grasp of the complexities of Dalit ife as a total insider and his path finding search for indigenous narrative modes and styles.

Devanur is widely recognised as a Dalit writer. This is as it should be. But it would be a grave error of judgement if we miss the wider significance of his work. For the first time in Kannada a Dalit writer has succeeded in holding to public gaze the life of his community which had melted into darkness hut while doing so, he has tackled the most vital issue of our times, that of survival and the problems arising out of it. What strikes us most when we look at his work as a whole is the progress he has made from a Dalit centred vision to a grasp of the life of society as a whole. The process is seen unfolding in his very first work ‘Dyavanuru’. ‘Ondu Dahanada Kathe (Story of a Funeral), ‘Datta’ (Given Away) and ‘Amasa’ deal exclusively with dalit experience. In ‘Marikondavaru’ (Those Who Sold Themselves) and ‘Grastaru’ (The Caught) non-dalit characters appear but their role is just symbolic. Kittappa and Gowda in Marikondavaru symbolise the exploiting class which kills with kindness. ‘Mudalaseemeli Kole Gile Ityadi’ (Murders etc. in Mudalaseeme) is more open than the other stories in the collection. The central character of the story is a Dalit but the social ambit of the story is much larger. ‘Dambaru Bandudu’ (The Aival of Tar) stands out from the other stories in the collection because of the larger interests of the writer who is now concerned with the changes taking place in his rural environment.

In ‘Odalala’, Devanur’s best known work, the focus is on the life of a Dalit family but the outer world, in the form of Sahukar Ettappa from whose mill Kalayya lifts a bag of groundnut and the police who raid Sakavva’s house in search of the stolen bag, forces itself on our consciousness. The gap between the two worlds is almost unbridgeable as the unbroken secret of ‘Odalala’, the depths of hunger, symbolizes. Members of Sakavva’s family have an advantage over their oppressors because they know their ways but the police fail to solve the mystery of the missing bag because they have no instruments to measure the depths of hunger. From this point of view, ‘Kusumabale’ Devanur’s second novel, marks a step forward. The adventures of Yada, an upper class individual, are as much the focus of the novel as the adventures of Amasa, the Dalit.. The central event of the novel, the union of Channa and Kusuma, is not just a stray incident but repetition of a historical parterns of the Dalit and non Dalit relationship. as Kuriyayya truly visualises.

Odalala presents two contrasting states of Sakavva’s family. It is this contrast that generates the ironic vision of the novel. The first five sections provide pictures of relationship within the family, which is broken up into three units, but still maintains a sort of domestic solidarity under the stewardship of Sakavva, the head. As she appears before us at the beginning of the novel, Sakavva is a bit flustered by the disappearance

of a cock which belongs to her. But she is a proud woman. When Sannayya, her second son presses for his share in the family property, she fires back: “What did you say? say it again… You press for your nights, do you? This is my property, understand? I have earned it with my own hands. I was born a woman, all right, but no man could beat me

in hard work.” She ridicules Kalayya, the eldest son, who has failed in his duty of keeping the family together and takes Sannayya to task for allowing himself to be dictated to by his wife. But she has real affection for Gouramma, wedded to an irresponsible idler, and Gauramma’s sons, the sickly ‘Duppaty Commissioner’ and Shivu and her young daughter Puttagowri. When she anncunces that she would leave all her property to Shivu, Sannayya and his wife Chaluvamma who have an eye on it, burst with anger. Kalayya who has no children of his own is saddened by the whole drama. Shivu and Puttagowri, oblivious to the domestic strife,busy themselves drawing pictures of peacocks on the walls. Sakavva finds immense solace in dreaming of her grandson’s future. The gloom temporarily lifts when Kalayya brings home a bag of ground nut stolen (that is now how he sees it) from Ettappa’s mill. The whole family is united in the unexpected feast. Domestic solidarity prevails over petty differences and quarrels. Even a neighbour who makes her casual call has her share. This scene of solidarity has a great symbolic significance in the novel.

The arrival of the police on the scene changes the situation radically. Sakavva’s family loses its dignity under the reductive authority of the representatives of the law if Sakavva falls from her domestic eminence and becomes comic. The language too changes. The humiliation of Shivu and Puttagowri at the hands of the police is presented in serious and pathetic tones but the predicament of the officers of law who are unable to solve the mystery of the missing bag invites irony and comedy. Sakavva who seeks the help of her persecutors to get back her lost cock becomes an object of pity and ridicule.

Odalala was a tremendous success when it appeared and it has now assumed the stature of a modern classic. But ‘Kusumabale’, though experimental in nature, is of greater significance in the context of Dalit writing. No other Dalit writer has shown such a sure grasp of the entire culture of a society as Devanur has shown in this novel. We will have to go to African writers like Wole Soyinka in search of parallels.

Odalala and Kusumabale differ in their temporal and spatial coverage. In Odalala Devanur concentrates on a few hours in the domestic life of Sakavva’s family and the action is limited to the goings on in her own house. ‘Kusumabale’ spreads over past. present and future and includes in its structure what Soyinka has called the ‘fourth dimension’. The events that take place in the Holageri, the untouchable colony, are limited to the present, but the relationship between Yada and Akkamahadevi involves the events of the past as well. The children in the story-Kusuma’s baby and the child in Kempi’s womb- belong to the future. And the dialogue between the Jivatma and the Cot, the comments of Jotammas and the rituals of birth and death belong to the fourth dimension. The metaphysical suggestions are as important as the physical details in the novel. This inclusive vision is unique to Kusumabale in all of Devanur’s work.

Devanur’s artistic achievement in this novel is as striking as its cultural exploration. Perhaps the most decisive factor in Kasumabale is the choice of a narrator who speaks from within the community and has the ability to articulate its complex life. The narrator’s sensibility is the sensibility of the whole novel. It is a sensibility which is open to all kinds of experience. The innocent joy of children like Parsad, the touching sorrow of the lives of Kusuma and Iri, the adventures of Yada, Gurusidmava and others who fight against the forces of oppression though they are not strong enough to do so and so on. This sensibility defies restrictive social codes and responds to life in all its forms. The integral relationship between the narrator’s sensibility and the community he presents is reflected in the narrative mode that the novel creates for itself. The narrator employs several forms of folk narration in the management of his narative. The language of the novel too has the same flexibility. When the narrator appears in the role of an inspired singer, for example, his language crosses the boundaries of prose and becomes poetry. But it can also cope wilth humorous and ironic situations and drama. ‘Kusumabale’ is an important step towards the resolution of the conflict between Western and native narrative modes, which has existed throughout the career of the modern Kannada novel.

Finally, a word about the nature of revolt in Devanur’s novels and stories, since this question always crops up in discussion of Dalit writing. Revolt or protest in Devanur’s work is a complex thing because it is not limited to characters and events that articulate it directly. In fact Devanur has a marked preference for structures which present Dalit life in all its complexity and force the reader to articulate the implicit protest for himself. Normally the characters who articulate protest directly in his stories are people who have had the benefit of education as in ‘Grastaru’ and ‘Marikondavaru’. But Devanur is more effective when he leaves the responsibility of articulating protest to the sensibility of the reader as in the story ‘Mudalaseemeli Kolegile ltyadi’ which reminds me of Shankararao Kharat’s famous Marathi story, ‘Sangava’. Unlike in the work of Black American writers- Richard Wright’s ‘Native Son’ for example -protest never manifests itself in violent forms in Devanur’s fiction. This is probably because of the difference between the two social contexts.